ARON WIESENFELD:

LIMINAL STATES

David Molesky

Portrait by Monica Wiesenfeld

Aron Wiesenfeld’s work immediately triggers childhood memories of my explorations into the woods of suburbia. Wandering these fringe landscapes between civilization and wilder nature, I forged new territories while discovering myself. In the stillness of being alone in nature, we can watch our own thoughts as moods drift by like clouds. Aron’s work perfectly captures these mind states, blurring the boundary between his art and personal reflections.

“Communing with nature” is the colloquial reference we use for the universal emotional or spiritual response we often have outdoors. Aron sets a stage by often dwarfing the scale of his figures within enormous spaces. His youthful subjects seem caught in a melancholy of reflection and realization as they stare off into the enigmatic abyss. Child psychologist David Elkind describes the concept of “personal fable,” when adolescents commonly have experiences of “irreparable sadness,” believing that no one has ever felt the way they do. When I was younger and felt upset, I would often escape into the woods, amazed at how quickly I could be reconstituted by simply staring at patterns of leaves and plants, and hearing a forest rustle as a wind passed by.

Nature is both healer and teacher. Out of its immensity, awareness of a greater sense of connectedness whispers to us. These revelations are capable of elevating nearly anyone out of a rut of detached despair. Perhaps this is why, in the Renaissance, melancholia was a revered trait, and the people affected by it were considered to be closer to God. You may have noticed that religious music is always in a minor key. Most of us experience some kind of normal emotional growing pains as we transition from child to adult. Nowadays, some parents seem to forget their own childhood and react to their children’s trials with prescriptions of Prozac, Adderall, and other pharmaceutical inventions. Nature is a more effective, pleasant pill to swallow. To feel small, and to realize our place within a larger ecosystem helps give appropriate scale to smaller upsetting events. It’s hard to make mountains out of molehills in the face of real mountains.

The fragility of Aron’s innocent youth conjures concern and empathy. Their bodies verge on sexual, but gangly limbs and oversized features secure them in the world of childhood. Even those carrying the markers of the adult—a briefcase, a string of pearls, breasts and hips—read childlike with their opaline skin and rounded foreheads. Their heavy eyelids with an indiscernible stare help transport us into their inhabited landscapes and psychological worlds. The universal appeal of a child’s face also adds to the projection into our own childhoods. Aron creates soft, fictional fairy tales about lingering adolescence.

The landscapes in Aron’s paintings are also stylized. He takes the time to carefully paint each leaf and blade of grass with finesse and delicacy through confident applications of paint. The tactile and sensual understanding of the plant shapes and textures makes the landscape believable as an extract from reality, enhancing our scrutiny of the painting’s main character. Like a master chef balancing flavors, Aron creates a perfect visual feast, pairing subtle color palettes with suggestive narratives, atmospheres and moods.

Aron’s work is a hybrid that occupies the liminal space between illustration and traditional painting. His ability to mimic an array of surfaces and materials carries on the tradition of many great landscape painters. His rendering of detail brings to mind Durer’s Great Piece of Turf from 1503, and John Ruskin’s Victorian ideas about the careful observations of nature. His paintings of lone figures, gazing into vacuous space are in the family with Caspar David Friedrich’s painting Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818. The pastoral narrative painter, Nicolas Poussin, was one of the first to visually show the concept that “the tragedy of mankind is small in the big nature” in his seventeenth-century painting Landscape with a Man being Killed by a Snake, 1648.

These paintings transmit real, sincere, emotional states where we can project ourselves. Perhaps it is the exercise of having empathy for these deeply melancholic figures that fortifies us to face the truth and inevitably of the loneliness of our existence. It is counterintuitive that pleasure might come from feeling empathy for a person or a figure in a painting whom we recognize as going through a difficult experience. And yet, I find myself pleasantly immersed in Aron’s paintings, returning to them because of that unexpected jolt of pleasure/pain. Merging his imagination with techniques that harken back to Old Master painters, Aron builds compositions that powerfully transmit mood and childhood nostalgia.

I caught up with Aron at his studio in San Diego as he made the final touches on works for his first solo exhibition with Jonathan Levine Gallery in NYC, his ninth solo show in ten years.

David Molesky: I recently discovered that your painting was on the cover of a poetry book. How did that come about, and were the poems written about your paintings?

Aron Wiesenfeld: There is a book of poems and paintings that I made in collaboration with Bruce Bond, or I should say he made it. Bruce was a collector of my work and we talked a lot about art and books. I asked if he would ever want to do a collaborative project, not really knowing what that might look like. Three days later, he sent me a poem based on one of my paintings, and maybe forty days after that, he had written enough poems (all based on my paintings) for a whole book. It was really fast. I was so happy to see what he had written. Every poem had a progression that started with the image, and went off somewhere with it. It expanded the time and space of the painting.

Have you made paintings based on poems?

I’ve been inspired by poems, but I never did a painting based literally on a poem. It would be an interesting challenge. I wouldn’t want to make an illustration of it. Maybe it could be liberating; I think I would want the art to be about a feeling rather than the story. It’s not poetry, but I love the drawings Balthus did of Wuthering Heights. They are really emotional.

Taking a closer look at your new painting, Bunker, it looks like you’ve painted the foliage on top of a warm brown underpainting.

That painting was a little different as far as the approach because I wanted something really specific with the foliage. I started with a couple layers of dark brown and green paint, scumbled roughly to have a texture underneath. Then I painted the plants that were close to the ground, and last, the shoots that came up above. It is detailed, but the texture underneath gives it the impression of being more detailed than it actually is. I love the way Waterhouse paints foliage, very loosely, but with a few sharp areas—the eye creates the rest of the information.

What’s your general process for developing an image? Where do the ideas come from, and how do you capture and develop them into paintings?

Ideas come from anywhere… places, memories, movies, art, etc. A book called Art and Fear said, “Notice what you notice.” I thought that was great advice. So many times something that flashed by my consciousness might be lost just as quickly. There is a kind of discipline to saying, “Wait, there was something interesting there, what was it?” Memory is so transitory; it’s hard to keep an idea in my mind when that happens. I want to get to my sketchbook as quickly as I can. It’s difficult to sketch that inspiration and replicate the thing that was interesting in the first place. But then the sketches evoke other ideas too, so I end up doing a lot of sketches at a time.

When starting a painting, I usually work from a sketch that I like. It’s painted as much as possible from imagination and memory. A lot of times, I will get an idea of a better image along the way, and make some drastic changes, sometimes destroying weeks of work. The paintings are usually started with no color, just value, to get the forms and the light, and color is added at the end.

I love your charcoal drawings. What is your method for making these?

The charcoals are really fun to do, and come more naturally than oil painting. I tape a big sheet of toothy paper to a panel and cover it with rubbed-on vine charcoal to get a medium-grey tone. Then I erase out the lights to start getting the form (usually a figure) and add some soft vine charcoal shapes for the dark areas. I keep it in that loose state of big shapes until it looks good, and then go in with details using charcoal pencil and compressed charcoal for deeper darks. It’s a great medium because it’s so easy to make changes, and very quick to bring it to a finished state. That malleability is also its drawback, though, as the finished drawing is very fragile.

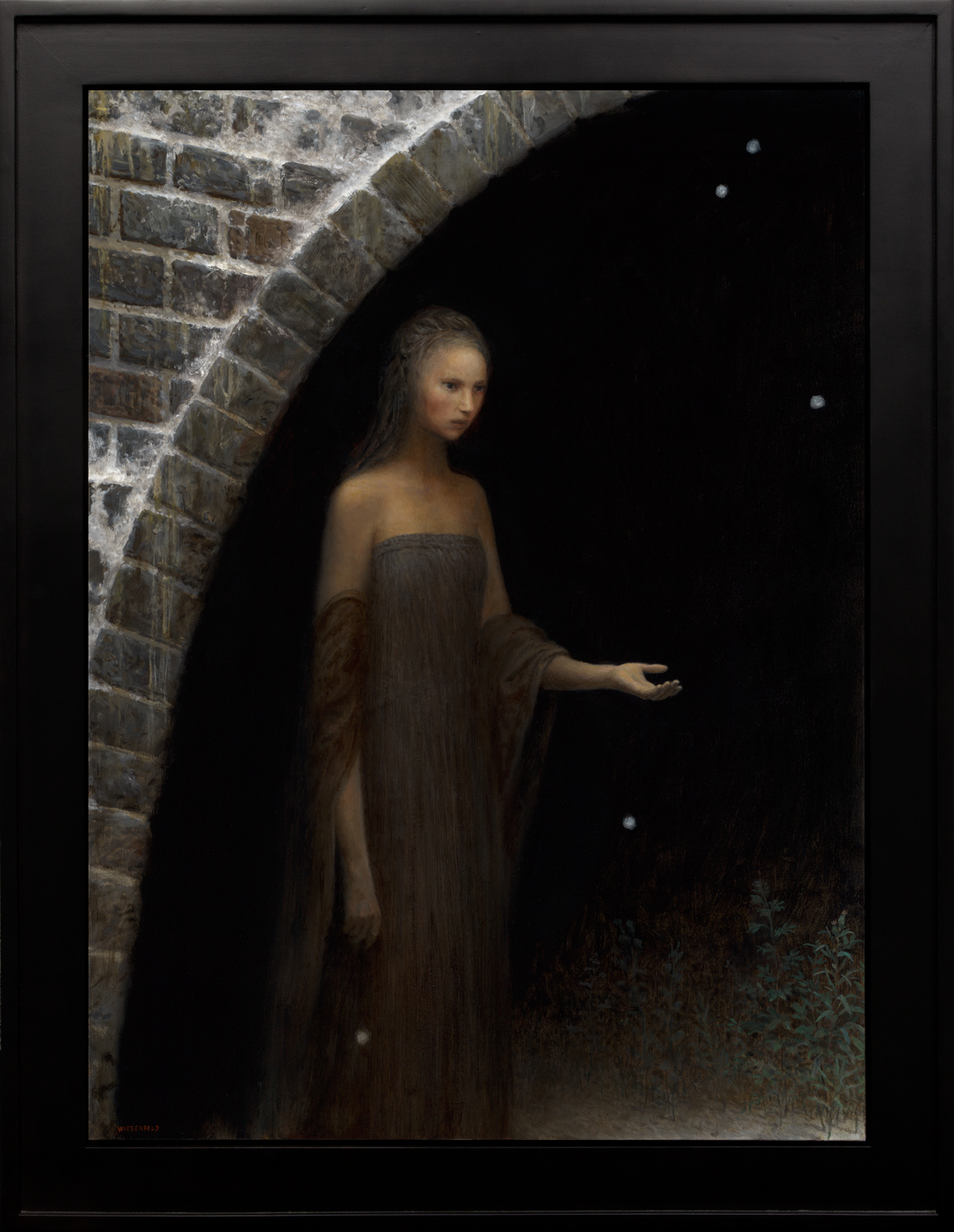

What were you going for in Night Grove? I love that sense of imagined presence that we feel lurking in the dark that makes us fearful to look.

I think presence is the right word. It’s not a question of “what” is in there, but “who.” I think a dark entryway is a very potent symbol that can evoke a lot of things; it’s a matter of the mind filling in the blanks. Probably the first thought is that it’s something threatening, but it doesn’t have to be. It’s like the Jungian shadow—it’s all the things you can’t accept about yourself, the bad but also the good, including your own greatness.

Have you ever been psychoanalyzed? Or have you ever had a child psychologist study your work?

I was in analysis for years. I learned that the unconscious is not just a sleepy, animal level of thought, but it’s really a second mind underneath, just as intelligent as the one on top, with its own personality and agenda. So in the dark places, that’s the unconscious. Dreams are a good way to access the unconscious, and painting is also. Once you let the unconscious speak, the question is, what do you do with it? One of the main functions of analysis is to translate the dream, and receive a useful message from it. In art, it’s more ambiguous. I think it’s enough to simply let it out and say to the audience, “Here’s what I got, make what you will of it.” My analyst wanted to interpret my paintings like dreams, but I resisted because I don’t want them to be reduced like that. A dream is a problem to be solved, but for painting to have any universal relevance, it should be an open question.

Do you think it is possible that these are actually self-portraits?

Yes, I think they are. They are how I feel, and my memory of how I felt when I was younger. It’s often an internal thing, a deep feeling of doubt, uncertainty, and not knowing what to do. Female figures seem to express that best for me most times. I don’t know why.

What does the lone figure in the landscape mean to you personally?

It means that we are all alone, always. “The world” will never be anything other than the perception of my own senses. I personally was aware of that more acutely, maybe more than is usual, that sense of being separate.

What do you think elongating the figures does to the viewer’s experience?

Right off the bat, it says that it’s a fantasy. The painting is not trying for an imitation of reality, so I suppose it gives me some license, and tells the viewer that he or she doesn’t need to judge it on that criteria. But it adds a responsibility in the sense that, with any stylized alteration like that, the artist is saying, “This is my world,” and it has to have its own logic and believability. I didn’t set out to make elongated figures. I set out to make figures that were constructed from imagination, so there were going to be oddities to them. When I started painting, I gave a lot of thought to what the medium of painting could do that was unique, that other mediums like photography couldn’t. My thought was that I could make them unique by putting realism into an invented armature, if that makes sense. In other words, give my fantasy world as much verisimilitude as possible to try to create a world that was different but logical as well. I’m not sure I ever really succeeded, but that was the intention.

Originally featured in the January 2017 issue of Juxtapoz Magazine