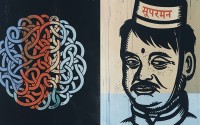

It’s easy to mistake Gary Taxali for a foreigner, arriving from some other time, some other place. His illustration style feels distantly familiar, like a font or a character clipped from a generation you haven’t lived. His work goes exhibited in the United States and overseas, or tied into commercial exploits in such natural and winking ways you’re sure his mark has always been there, sewn right into the brand. And then there’s the aspect of his success, a kind we don’t associate with ourselves, too often — designing the covers of the New York Times, Esquire, Rolling Stone, GQ, and Playboy, or the cover of an Aimee Mann album; a commercial success. But Taxali, the acclaimed illustrator, designer, and artist who’s managed to deftly navigate the arenas of contemporary art, commissioned illustration, and collaborative commerce, remains one of our own. Born in India, Taxali arrived to Canada as a child, and has held his home here ever since. Working from a large complex of studio spaces in Toronto’s west-end, he continues his prolific production of paintings and objects marked by his singular Depression-era advertising aesthetic that most recently extended to the Whitney Museum of Art and Harry Rosen for unique design commissions.

Taxali’s most recent endeavor, “Shanti Town,” pushes the artist to new territory still. Marking the first “pop up exhibition” at Waddington’s auction house, it puts a decade of Taxali’s work on display, much of it for the first time in Canada. Taxali again attracted to thresholds, he titled the exhibition after a dual meaning: “I first knew the word ‘shanty’ in Hindi, and it means ‘peace’,” he explains. The “1930s Depression-era signs, posters, packaging, and graphics have always served as a large mood inspiration for my art […] the paradoxes of human relationships, love, isolation, period advertisements, propaganda, and economic despair and frustration — all recurring themes in the works presented in this show. Yet, there is also a recurring sense of acceptance of ‘what is’ in every piece. This is where I cannot escape from humor. While it mocks the worst parts of the human condition, it also binds us to a shared understanding that life should never be taken too seriously. I simply cannot think of a more peaceful way to be than that."

BLOUIN ARTINFO Canada sat down with Taxali to discuss the formative associations he carries through his significant body of work, his relationship to Warhol, to abstract expressionism — and the complicated position he’s assumed, standing at the brink of commerce and art.

Were you looking through your catalogue with a desire to produce a certain narrative for this show, or did the framework arrive later?

You know, kind of both. There’s a natural narrative that I’ve always been exploring in the pictures I make, where my exhibitions are always like part one, part two, part three. It’s automatically there, and it harkens back to my illustration background. I can’t skip the storytelling thing. As I look at the images, there’s a thing that’s going on here. There’s certain themes, there’s a conversation happening.

But everything I do is a self-portrait. I think everything any artist does is a self-portrait. You’re using the medium to say something, but it’s really you. I think mapping things out destroys the freshness of ideas.

How consciously are you navigating a different aesthetic between your illustration work and your “fine art,” as you put it?

Illustration is insecure about fine art, and fine art is insecure about illustration. They love each other, they have a weird relationship to one another, but I don’t think they’ll ever truly come together. I try to make no difference in the way I work; I draw the way I draw. But the coming together of it has given me a point of view.

I can’t understand how artists do things without being conscious of the importance of communicating with the viewer. I think an illustration must communicate — but I also think a piece of fine art should as well.

But arguably there are lots of ways to communicate — not just with dialogue or clear narrative action.

I absolutely agree; my favorite artists are the abstract expressionists. The things I like the most in other people’s work are non-narrative, non-contextual things. They are doors to dialogue, to discussion, to ideas. It makes them the best communicators.

Straightforward applications of storytelling haven’t been in fashion for some time, in the contemporary artworld; you must know this better than most, teaching at an art school. How do you regard this narrative form falling out of favor?

I think it’s been this way since Warhol hit the peak; I wasn’t around then, but learning about him, and feeling heartbroken about his loss after he died … I can remember doing a series of ink paintings, at that time, and I took products and crushed them, and then did really tight renderings of them. I don’t know why. I was fifteen and heartbroken. But all this to say that he was a commercial artist who said “here is a template for looking at art,” and in many ways I think the artworld has learned nothing from it. They glorify what his message was, but at the same time turn their back on everything he accomplished. Imagine a human being reaching that point, and exposing communication for what it is, and then turning it on itself, making the brute ugliness and the purpose of it the most beautiful thing … how can anybody not use this as a template, and say “let’s rethink some things”? It’s like he faded away, and postmodernism screwed everything up again.

Any degree of success I have — and my colleagues have — is because of him. There is an environment for us to thrive in.

Where did your visual language come from?

My childhood. The things that shaped me have never left me. I have no real interest in moving beyond those, not right now, anyway. My disdain for the education system, and doodling on books and things, made me realize how nice it was to turn things that were supposed to be ugly into things that could be beautiful, or looked at more than twice. I still like that notion. Cartoons were an influence, like the Fleischer brothers, Betty Boop, Coco the Clown, Felix the Cat. At the same time I hate comic books, I have no interest in the sequential story; but I love the animations, and the still image.

Do you regard your catalogue of work as a form of nostalgia, then?

No. I use my childhood as a kind of reference, but if it was nostalgia, I would be telling stories about my childhood or things of that time; I’m more interested in what’s happening in this moment. I keep topical themes and subject matter and things I am going through as an adult … I don’t want to talk to children. I even wrote and illustrated a children’s book, and it wasn’t for them. It was a book for me.

Having heard you gesture so admiringly to Warhol, I’m guessing you’re quite comfortable with the intersection between art and commerce. A lot of your work takes place at that threshold — you mentioned Harry Rosen designs, for instance; and you’re “popping-up” at Waddington’s, a central site of the art market. How do you reflect on — and navigate — the intersection between art and commerce?

All artists, we look at it as a necessary evil. When you get too caught-up in it, it messes with your mind. But then there are other times where it highlights what you do, and makes things easier. It also has the potential to challenge us. For instance, with public installations that take my work and put it on signs and in commercial spaces … it was interesting to have to work on that scale, despite the fact that no one is disguising its purpose as a banner or a sign, in that moment. I was challenged, but not compromised.

But I’ve been lucky — the people that I’m working with have come to me and said, “you do this thing. Can we work together, where you still do this thing, but we complement it by putting it in this form?” I say, “Ok.” No one is changing who you are, in that situation, nor am I compromising. That level of commerce, I say bring it on.

– See more at: http://ca.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/1005959/interview-gary-taxalis-commerce-finds-art#sthash.kTUTyex5.dpuf

It’s easy to mistake Gary Taxali for a foreigner, arriving from some other time, some other place. His illustration style feels distantly familiar, like a font or a character clipped from a generation you haven’t lived. His work goes exhibited in the United States and overseas, or tied into commercial exploits in such natural and winking ways you’re sure his mark has always been there, sewn right into the brand. And then there’s the aspect of his success, a kind we don’t associate with ourselves, too often — designing the covers of the New York Times, Esquire, Rolling Stone, GQ, and Playboy, or the cover of an Aimee Mann album; a commercial success. But Taxali, the acclaimed illustrator, designer, and artist who’s managed to deftly navigate the arenas of contemporary art, commissioned illustration, and collaborative commerce, remains one of our own. Born in India, Taxali arrived to Canada as a child, and has held his home here ever since. Working from a large complex of studio spaces in Toronto’s west-end, he continues his prolific production of paintings and objects marked by his singular Depression-era advertising aesthetic that most recently extended to the Whitney Museum of Art and Harry Rosen for unique design commissions.

Taxali’s most recent endeavor, “Shanti Town,” pushes the artist to new territory still. Marking the first “pop up exhibition” at Waddington’s auction house, it puts a decade of Taxali’s work on display, much of it for the first time in Canada. Taxali again attracted to thresholds, he titled the exhibition after a dual meaning: “I first knew the word ‘shanty’ in Hindi, and it means ‘peace’,” he explains. The “1930s Depression-era signs, posters, packaging, and graphics have always served as a large mood inspiration for my art […] the paradoxes of human relationships, love, isolation, period advertisements, propaganda, and economic despair and frustration — all recurring themes in the works presented in this show. Yet, there is also a recurring sense of acceptance of ‘what is’ in every piece. This is where I cannot escape from humor. While it mocks the worst parts of the human condition, it also binds us to a shared understanding that life should never be taken too seriously. I simply cannot think of a more peaceful way to be than that."

BLOUIN ARTINFO Canada sat down with Taxali to discuss the formative associations he carries through his significant body of work, his relationship to Warhol, to abstract expressionism — and the complicated position he’s assumed, standing at the brink of commerce and art.

Were you looking through your catalogue with a desire to produce a certain narrative for this show, or did the framework arrive later?

You know, kind of both. There’s a natural narrative that I’ve always been exploring in the pictures I make, where my exhibitions are always like part one, part two, part three. It’s automatically there, and it harkens back to my illustration background. I can’t skip the storytelling thing. As I look at the images, there’s a thing that’s going on here. There’s certain themes, there’s a conversation happening.

But everything I do is a self-portrait. I think everything any artist does is a self-portrait. You’re using the medium to say something, but it’s really you. I think mapping things out destroys the freshness of ideas.

How consciously are you navigating a different aesthetic between your illustration work and your “fine art,” as you put it?

Illustration is insecure about fine art, and fine art is insecure about illustration. They love each other, they have a weird relationship to one another, but I don’t think they’ll ever truly come together. I try to make no difference in the way I work; I draw the way I draw. But the coming together of it has given me a point of view.

I can’t understand how artists do things without being conscious of the importance of communicating with the viewer. I think an illustration must communicate — but I also think a piece of fine art should as well.

But arguably there are lots of ways to communicate — not just with dialogue or clear narrative action.

I absolutely agree; my favorite artists are the abstract expressionists. The things I like the most in other people’s work are non-narrative, non-contextual things. They are doors to dialogue, to discussion, to ideas. It makes them the best communicators.

Straightforward applications of storytelling haven’t been in fashion for some time, in the contemporary artworld; you must know this better than most, teaching at an art school. How do you regard this narrative form falling out of favor?

I think it’s been this way since Warhol hit the peak; I wasn’t around then, but learning about him, and feeling heartbroken about his loss after he died … I can remember doing a series of ink paintings, at that time, and I took products and crushed them, and then did really tight renderings of them. I don’t know why. I was fifteen and heartbroken. But all this to say that he was a commercial artist who said “here is a template for looking at art,” and in many ways I think the artworld has learned nothing from it. They glorify what his message was, but at the same time turn their back on everything he accomplished. Imagine a human being reaching that point, and exposing communication for what it is, and then turning it on itself, making the brute ugliness and the purpose of it the most beautiful thing … how can anybody not use this as a template, and say “let’s rethink some things”? It’s like he faded away, and postmodernism screwed everything up again.

Any degree of success I have — and my colleagues have — is because of him. There is an environment for us to thrive in.

Where did your visual language come from?

My childhood. The things that shaped me have never left me. I have no real interest in moving beyond those, not right now, anyway. My disdain for the education system, and doodling on books and things, made me realize how nice it was to turn things that were supposed to be ugly into things that could be beautiful, or looked at more than twice. I still like that notion. Cartoons were an influence, like the Fleischer brothers, Betty Boop, Coco the Clown, Felix the Cat. At the same time I hate comic books, I have no interest in the sequential story; but I love the animations, and the still image.

Do you regard your catalogue of work as a form of nostalgia, then?

No. I use my childhood as a kind of reference, but if it was nostalgia, I would be telling stories about my childhood or things of that time; I’m more interested in what’s happening in this moment. I keep topical themes and subject matter and things I am going through as an adult … I don’t want to talk to children. I even wrote and illustrated a children’s book, and it wasn’t for them. It was a book for me.

Having heard you gesture so admiringly to Warhol, I’m guessing you’re quite comfortable with the intersection between art and commerce. A lot of your work takes place at that threshold — you mentioned Harry Rosen designs, for instance; and you’re “popping-up” at Waddington’s, a central site of the art market. How do you reflect on — and navigate — the intersection between art and commerce?

All artists, we look at it as a necessary evil. When you get too caught-up in it, it messes with your mind. But then there are other times where it highlights what you do, and makes things easier. It also has the potential to challenge us. For instance, with public installations that take my work and put it on signs and in commercial spaces … it was interesting to have to work on that scale, despite the fact that no one is disguising its purpose as a banner or a sign, in that moment. I was challenged, but not compromised.

But I’ve been lucky — the people that I’m working with have come to me and said, “you do this thing. Can we work together, where you still do this thing, but we complement it by putting it in this form?” I say, “Ok.” No one is changing who you are, in that situation, nor am I compromising. That level of commerce, I say bring it on.

– See more at: http://ca.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/1005959/interview-gary-taxalis-commerce-finds-art#sthash.kTUTyex5.dpuf

It’s easy to mistake Gary Taxali for a foreigner, arriving from some other time, some other place. His illustration style feels distantly familiar, like a font or a character clipped from a generation you haven’t lived. His work goes exhibited in the United States and overseas, or tied into commercial exploits in such natural and winking ways you’re sure his mark has always been there, sewn right into the brand. And then there’s the aspect of his success, a kind we don’t associate with ourselves, too often — designing the covers of the New York Times, Esquire, Rolling Stone, GQ, and Playboy, or the cover of an Aimee Mann album; a commercial success. But Taxali, the acclaimed illustrator, designer, and artist who’s managed to deftly navigate the arenas of contemporary art, commissioned illustration, and collaborative commerce, remains one of our own. Born in India, Taxali arrived to Canada as a child, and has held his home here ever since. Working from a large complex of studio spaces in Toronto’s west-end, he continues his prolific production of paintings and objects marked by his singular Depression-era advertising aesthetic that most recently extended to the Whitney Museum of Art and Harry Rosen for unique design commissions.

Taxali’s most recent endeavor, “Shanti Town,” pushes the artist to new territory still. Marking the first “pop up exhibition” at Waddington’s auction house, it puts a decade of Taxali’s work on display, much of it for the first time in Canada. Taxali again attracted to thresholds, he titled the exhibition after a dual meaning: “I first knew the word ‘shanty’ in Hindi, and it means ‘peace’,” he explains. The “1930s Depression-era signs, posters, packaging, and graphics have always served as a large mood inspiration for my art […] the paradoxes of human relationships, love, isolation, period advertisements, propaganda, and economic despair and frustration — all recurring themes in the works presented in this show. Yet, there is also a recurring sense of acceptance of ‘what is’ in every piece. This is where I cannot escape from humor. While it mocks the worst parts of the human condition, it also binds us to a shared understanding that life should never be taken too seriously. I simply cannot think of a more peaceful way to be than that."

BLOUIN ARTINFO Canada sat down with Taxali to discuss the formative associations he carries through his significant body of work, his relationship to Warhol, to abstract expressionism — and the complicated position he’s assumed, standing at the brink of commerce and art.

Were you looking through your catalogue with a desire to produce a certain narrative for this show, or did the framework arrive later?

You know, kind of both. There’s a natural narrative that I’ve always been exploring in the pictures I make, where my exhibitions are always like part one, part two, part three. It’s automatically there, and it harkens back to my illustration background. I can’t skip the storytelling thing. As I look at the images, there’s a thing that’s going on here. There’s certain themes, there’s a conversation happening. But everything I do is a self-portrait. I think everything any artist does is a self-portrait. You’re using the medium to say something, but it’s really you. I think mapping things out destroys the freshness of ideas.

How consciously are you navigating a different aesthetic between your illustration work and your “fine art,” as you put it?

Illustration is insecure about fine art, and fine art is insecure about illustration. They love each other, they have a weird relationship to one another, but I don’t think they’ll ever truly come together. I try to make no difference in the way I work; I draw the way I draw. But the coming together of it has given me a point of view. I can’t understand how artists do things without being conscious of the importance of communicating with the viewer. I think an illustration must communicate — but I also think a piece of fine art should as well.

But arguably there are lots of ways to communicate — not just with dialogue or clear narrative action.

I absolutely agree; my favorite artists are the abstract expressionists. The things I like the most in other people’s work are non-narrative, non-contextual things. They are doors to dialogue, to discussion, to ideas. It makes them the best communicators.

Straightforward applications of storytelling haven’t been in fashion for some time, in the contemporary artworld; you must know this better than most, teaching at an art school. How do you regard this narrative form falling out of favor?

I think it’s been this way since Warhol hit the peak; I wasn’t around then, but learning about him, and feeling heartbroken about his loss after he died … I can remember doing a series of ink paintings, at that time, and I took products and crushed them, and then did really tight renderings of them. I don’t know why. I was fifteen and heartbroken. But all this to say that he was a commercial artist who said “here is a template for looking at art,” and in many ways I think the artworld has learned nothing from it. They glorify what his message was, but at the same time turn their back on everything he accomplished. Imagine a human being reaching that point, and exposing communication for what it is, and then turning it on itself, making the brute ugliness and the purpose of it the most beautiful thing … how can anybody not use this as a template, and say “let’s rethink some things”? It’s like he faded away, and postmodernism screwed everything up again. Any degree of success I have — and my colleagues have — is because of him. There is an environment for us to thrive in.

Where did your visual language come from?

My childhood. The things that shaped me have never left me. I have no real interest in moving beyond those, not right now, anyway. My disdain for the education system, and doodling on books and things, made me realize how nice it was to turn things that were supposed to be ugly into things that could be beautiful, or looked at more than twice. I still like that notion. Cartoons were an influence, like the Fleischer brothers, Betty Boop, Coco the Clown, Felix the Cat. At the same time I hate comic books, I have no interest in the sequential story; but I love the animations, and the still image.

Do you regard your catalogue of work as a form of nostalgia, then?

No. I use my childhood as a kind of reference, but if it was nostalgia, I would be telling stories about my childhood or things of that time; I’m more interested in what’s happening in this moment. I keep topical themes and subject matter and things I am going through as an adult … I don’t want to talk to children. I even wrote and illustrated a children’s book, and it wasn’t for them. It was a book for me.

Having heard you gesture so admiringly to Warhol, I’m guessing you’re quite comfortable with the intersection between art and commerce. A lot of your work takes place at that threshold — you mentioned Harry Rosen designs, for instance; and you’re “popping-up” at Waddington’s, a central site of the art market. How do you reflect on — and navigate — the intersection between art and commerce?

All artists, we look at it as a necessary evil. When you get too caught-up in it, it messes with your mind. But then there are other times where it highlights what you do, and makes things easier. It also has the potential to challenge us. For instance, with public installations that take my work and put it on signs and in commercial spaces … it was interesting to have to work on that scale, despite the fact that no one is disguising its purpose as a banner or a sign, in that moment. I was challenged, but not compromised. But I’ve been lucky — the people that I’m working with have come to me and said, “you do this thing. Can we work together, where you still do this thing, but we complement it by putting it in this form?” I say, “Ok.” No one is changing who you are, in that situation, nor am I compromising. That level of commerce, I say bring it on.

http://ca.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/1005959/interview-gary-taxalis-commerce-finds-art

.jpg)